No mixed bathing, and no bathing without a machine, The Daisy, Crocus and Lily among the flowers of the local ferries. Hackney carriage stands, and a 621-foot tower at New Brighton. A village pump in Poulton and a Marine Parade in Seacombe. Horse-drawn fire engines and noisy smithies. All of them a part of the Wallasey of over a century ago, the Wallasey I have taken a look at in the pages of an old official guide.

The book I have been reading bears the date 1909.It was to be another year 1910 before the town was to become a borough and get its mayor.

Before it received its charter, Wallasey had as number one the Chairman of its District Council. In 1909 it was Mr. William Henry Robinson.

The District Council, formed in 1896, had 30 members. The clerk was Mr. H.W. Cook. Its offices were at the corner of Church Street and King Street, Egremont. The telephone number was, appropriately, Wallasey 1.

|

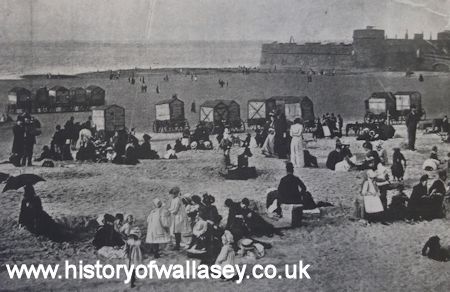

A busy scene on New Brighton beach with bathing machines in the background. |

In the year 1909 Princess Louise and the Duke of Argyle visited the Navy League Homes, in Withens Lane (the site of the former Technical College).

It was the year the Isle of Man steamer Ellen Vannin was lost just outside the Mersey with all hands (35).

In the newspapers of the time people were reading about Bleriot’s crossing the Channel by aeroplane, about the coming into force of old age pensions of 5s a week to men and women over 70.

The old book gives a picture of the town as it used to be. It is a picture pieced together by names and figures.

Captain Howard E. Martin was listed as ferries manager. The tramways department was headed by Major R.R. Greene.

The ferries had 11 steamers, the Daisy, Crocus, Thistle and Lily among them and a large barrage (Emily) and a dredger (Tulip).

A year’s ferry contract was 25s. A monthly contract was 2s 3d.

Luggage boats sailed every 40 minutes from Seacombe to Liverpool. Sailing times were “changed according to season and to meet the convenience and requirements of market gardeners and greengrocers.”

The town had a population of 73,000. The death rate was the lowest for years – 12.7 per 1,000.

There were 15 elementary schools (including St. Paul’s, St. Mary’s and Seacombe Wesleylan). The Education Department ran a house-wifery centre at 100 Littledale Road, Seacombe.

Formed just over 10 years before, in 1898, the public library in Earlston Road had branches at Demesne Street, in a shop at 374 Poulton Road, and at the corner of Leasowe Road and Wallasey Village. They were issuing about 225,000 books a year.

Bathing machines stood down on the sands, and there were regulations laid down for their use. You couldn’t bathe just anywhere more than a century ago.

Females could use the machines near Holland Road and Rowson Street stretches of the sea front. Males went to the Magazine Lane or Waterloo Road areas.

The rules included the following: “A person of the male sex, above the age of 12 years, shall not approach within 20 yards of any place at which any person of the female sex may be set down for the purposes of bathing, or at which any such person may bathe.”

It was forbidden to bathe without “tent, screen, shelter or bathing machine” between the hours of 8 a.m. and 8 p.m.

Boats could be hired for sailing on the clean, unpolluted waters of the Mersey. They coast 1s 6d per hour for three persons.

Horses and ponies could be hired on the sands for a shilling an hour. A donkey cost half of that.

There were hackney carriage stands at Seacombe Ferry, Egremont Ferry and New Brighton.

At New Brighton they had just knocked down the Ham and Egg Parade that had got the place a bad name up to 1907. Victoria Gardens was being put in its place.

The Tower still had its tower, 621 feet of it – then the tallest structure in the United Kingdom.

The Winter Gardens Theatre, just opened, was staging operas, plays and variety.

|

Tree-lined, little more than a muddy contry track, Seaview Road, Liscard, looked liked this at the turn of the last century. In the distance are the gates which stood near the junction with Hose Side Road. |

Poulton still had its village water pump and trough in 1909. They stood right in the centre of the cross-roads of Poulton Road, Mill Lane, Breck Road and Poulton Bridge Road.

Seaview Road, Liscard, was still a rough country lane, guarded on one side by a high brick wall.

Trafford House stood on the site of the old General Post Office in Liscard Village, and Mill Lane had a mill pond with a farmhouse on its banks.

Egremont had its long pier, its Hen and Chickens pub, and Garner’s Farm, in Rice Lane.

Seacombe had tightly-packed property known as the Mersey Street area, and a gateway in Birkenhead Road with the word @Marine Parade’ over it, carved on a painted board.

Oakdale Road was a dale and north from the top of Borough Road fields stretched away towards Liscard.

There were smithies in all parts of the town, noisy with the ring of anvils.

Horses drew the local fire engines. The stables were on the former site of the Capitol Cinema, Liscard.

There were weekend concerts in the old band stand in Central Park. There were one-man bands in the streets.

Poulton was famous for its long lanes of trees. Seacombe and Wallasey Village had small cottages with huge flower-filled gardens.

A map in the 1909 official year book shows fields and stretches of water that have long since been built over.

The trees have gone, and the cottages with the big gardens. The old stiles, wooden gates and manor houses of Liscard and Poulton have crumbled to dust.

World War One was to mark the beginning of big changes in the town. Wallasey was to branch out, stretch itself, give itself a new look.

The 1909 year book was to become museum stuff, and in its modest stuff, and in its modest way mirror social change.

It was published in the hey-day of the Edwardian ear, the time of long graceful dresses and hard bowler hats.

Featured sites

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Best Betting Sites

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Betting Sites That Are Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop