The Ferryboats That Sailed Off To War

The Iris and Daffodil were the twin sisters of the Wallasey Ferries that took an excursion into hell and came back glorious. They sailed off to war in naval grey, with an H.M.S. before their names. They took part in one of the great exploits in naval history. They limped home battle-scarred, and were awarded the designation ‘Royal’. From the quiet daily round of ferrying passengers across the Mersey, they went into the shells and minefields of ‘the first commando raid of all’ – and helped write a chapter in the story of World War One.

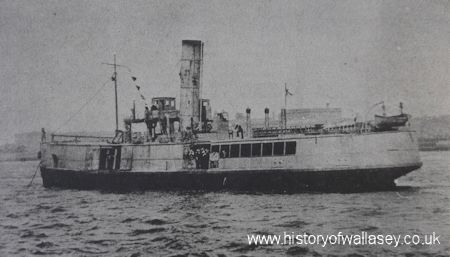

The ‘Iris’ and Daffodil’, twin-screw steamers, were built in 1906. The ‘Iris’ was 491 tons, the ‘Daffodil’ 482. Both were just over 159 feet in length.

They were the first vessels in the ferry fleet to sport a flying bridge and a promenade deck extending the full width of the ship.

Handsome-looking, they were an improvement on all that had gone before, with their three separate saloons on deck, with their graceful lines. For twelve years they ferried to and from Seacombe. A quiet, uneventful job.

They encountered nothing more dangerous than Mersey fogs. They became familiar, friendly sights.

Then, towards the end of World War One, they were taken over by the Admiralty. They were ‘called up’, like so many men from the town to which they belonged.

They were painted grey. They were manned by the Royal Navy. They went to war.

The Germans had occupied Zeebrugge, on the Belgian coast, in 1914. Owing to the wishes of the British Army, the mole and harbour works there were not destroyed by the British Navy before it withdrew.

It became a German submarine and destroyer base of the most formidable character. Immense concrete shelters gave a large measure of security.

The object of the British attack in 1918 was to block the Bruges Canal at its entrance into Zeebrugge Harbour. This was to be effected by sinking three old cruisers filled with cement.

As the cruisers had to pass batteries on the mole, it was first necessary to destroy the batteries.

The vessels chosen to carry the troops for this attack were the cruiser ‘Vindictive’ and the ferryboats ‘Iris’ and ‘Daffodil’ – which drew only eight feet six inches of water and therefore could be safety taken over minefields.

The night of April 22/23 was heavy and overcast when the naval force went into action under Vice-Admiral Keyes.

The ‘Vindictive’, commanded by Commander A.F.B. Carpenter, ran in, protected by smoke screens, through a storm of shells to the mole, with the ‘Iris’ and the ‘Daffodil’.

On reaching the mole at Zeebrugge the ‘Vindictive’s’ anchors failed to hold, and the captain of the ‘Daffodil’, although wounded, pinned the ‘Vindictive’ to the mole by manoeuvring into position against her.

The ‘Vindictive’s’ gangway were dropped, and the landing parties stormed across them. In order to keep in position, an enormous head of pressure had to be maintained in the ‘Daffodil’s’ boilers.

It was a strenuous effort for her engines. At one point the engine room was holed and two compartments flooded.

Meanwhile, the ‘Iris’ was making an unsuccessful attempt to land her troops. The scaling ladders would not hold.

Her captain decided to land his troops vis the ‘Vindictive’. But no sooner was his ship in position alongside her than the ‘Daffodil’ sounded the retirement, showing that the operation was complete.

The ‘Iris’, to the bitter disappointment of all on board, was instructed to cast off and make her way home.

Turning away northwards, the ferryboat came within range of the shore batteries and received hits which smashed the port side of her bridge and left her conning positions on fire.

She was by now well off course. Again and again she hit by gunfire.

Shells crashed through her sides and swept her decks. Her casualty figures rocketed from three to one hundred and fifty in a few minutes.

A single big shell plunged through the upper deck of the ‘Iris’. It burst below at a point where fifty-six Marines were waiting. Forty-nine of them were killed and the remaining seven severely wounded.

Another shell in the ward room, which was serving as a sick bay, killed four officers and twenty-six men.

The ferryboat limped on. The only thing which saved her was that Lieutenant G. Spencer, her navigating officer, badly wounded, had managed to correct her course in the split second before the shell landed. As the helm swung over, the ‘Iris’ answered.

She was able to set off her damaged smoke canisters and retire behind her own smoke screen, but not before three more shells from the heavy shore batteries had found their target.

Desperately crippled, with an appalling loss of life, a fire raging below her bridge, and with flooding in her forward compartments, she struggled home to Dover.

At Dover she found her sister ship, ‘Daffodil’, had been towed there by another vessel, the ‘Trident’.

|

"'Iris' and 'Daffodil' return at dawn from Zeebrugge after the fight", was the title of this painting done locally in 1918. They are shown steaming back to Dover. |

In a message to Wallasey immediately after the action, Vice-Admiral Keyes said: “Your two stout vessels carried blue-jackets and Marines to Zeebrugge and remained alongside the mole for an hour, greatly contributing to the success of the operation.

|

Iris and Daffodil at anchor with a tug after their return from naval service in 1918 |

“They will return to you directly the damage caused by the enemy’s gunfire has been repaired...”

Proudly reporting the role of the local vessels in the raid, the local news reported; “They said the accustomed paths of peace and ventured forth valiantly to face the dread perils of war.

“Wallasey, England’s youngest borough, has now an opportunity to put on record her share in the story of a great battle...”

The newspapers described the attack as “brilliant”, and the attack as “brilliant”, and the conduct of the two ferryboats from the Mersey as “gallant” in the extreme”.

|

Battle-scarred, the 'Iris' at anchor in the Mersey on May 17th, 1918, with bluejackets aboard her. |

The battle-scarred vessels sailed home to Wallasey on May 17th, 1918. The Mersey gave them a welcome fit for heroes.

Lifeboat rockets were fired from New Brighton as they dropped anchor off New Brighton Pier. The promenade was packed with sightseers.

Tram-cars were decorated for the occasion. Flags flew from every building.

A band played. Ships blazed their sirens in salute.

Officers and men were greeted by the Mayor, Alderman F.F.Scott, at Egremont.

The Mayoress was presented with a huge bunch of irises and daffodils by Lieutenant Stansfield, the only officer of the ‘Iris’ to survive the action.

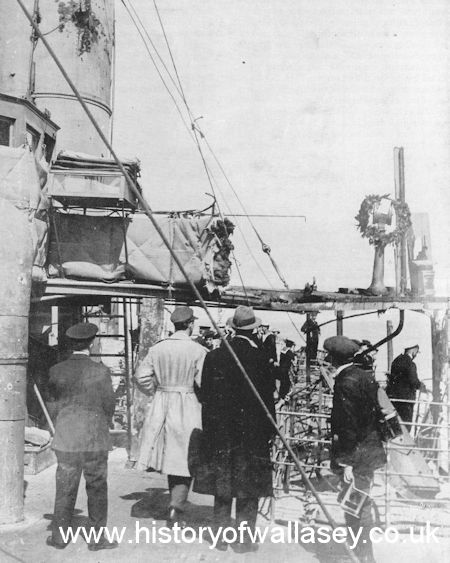

For two days both vessels were berthed at Canning Dock. Thousands of people visited them there.

For their heroic service the ferryboats were given the designation ‘Royal’.

|

After theie return from Zeebrugge, the two vessels were put on public show in Liverpool before their damage was repaired. Visitors view the promenade deck of Iris. Note the damaged bridge and the wreath in tribute to the fallen. |

The shrapnel-ridden funnel of the ‘Iris’ stood for many years on the south side of Seacombe Ferry as a memorial. Her bell hung in the ferry vestibule for many years. The bell now stands proudly outside Earlston Reference Library.

For years they continued to serve the ferries. Then, in 1931, the ‘Royal Iris’ was brought for use as a cruise steamer at Dublin. In 1933 the ‘Royal Daffodil’ was sold to the Medway Steam Packet Company. After several years’ service on the Thames she was sold for scrap.

Eventually, the ‘Royal Iris’ went to Cork Harbour and was renamed ‘Blarney’. She was broken up in 1938

From the 1920’s a commemorative service had been held aboard a Wallasey ferryboat on the Sunday nearest to St. George’s Day. Survivors of the action use to travel to Wallasey for the occasion

Featured sites

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Best Betting Sites

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Betting Sites That Are Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop